Jerry Crasnick

ESPN Senior Writer

Even in a baseball enclave with the provincial tenacity of Cincinnati, tradition is powerless against the march of time.

Crosley Field and its endearing quirks gave way to Riverfront Stadium and its concrete sameness, until Great American Ball Park’s 2003 debut marked a return to the good old days. The traditional season opener, hosted exclusively by Cincinnati until 1989, is now shared with 29 other teams. And the careers of even the most revered heroes come with an expiration date; Ted Kluszewski’s biceps gave way to Pete Rose’s headfirst slides and Barry Larkin’s sustained brand of excellence, until the new millennium arrived and Ken Griffey Jr. and Joey Votto took over as the faces of the franchise.

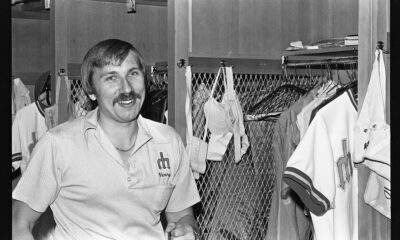

Amid all that change, it’s been a comfort to generations of Reds alumni to know they could drop in on a familiar sight: clubhouse manager Bernie Stowe, making sure clean uniforms were hung by the lockers with care. Or brushing the mud from spikes and polishing them to look like new in anticipation of tomorrow’s game. Or doing any of the other mundane, seemingly thankless chores that allow a man to make a living and build a legacy.

Few baseball fans outside Cincinnati have ever heard of Bernie Stowe or have reason to appreciate the depth of his contributions to the Reds since he joined the team as a bat boy in 1947. But for scores of Reds players, coaches and managers, he was synonymous with the concept of organizational loyalty and baseball team-as-family.

Stowe, who died Tuesday at age 80, was one of those behind-the-scenes contributors who tended to the daily routine that keeps an organization running. He took part in 67 Opening Days in Cincinnati until his retirement in 2014. At the rate of 15 hours per day, the pay was miniscule. But Stowe would be the first to admit he was stealing money, because it never felt like work.

“There was not one day I ever came to the park and Bernie Stowe wasn’t in a good mood, or cracking jokes, or busting chops,” said Sean Casey, who played first base in Cincinnati from 1998 to 2005. “He loved being at the yard every day, and he loved taking care of you and being there for you. He made you feel like life is good and you’re fortunate to be doing what you’re doing. I could go on for days about how wonderful a man he was.”

I came to know Stowe — and by extension, his family — during my five years as the Reds beat reporter for the Cincinnati Post at the height of the Pete Rose-Marge Schott insanity. He was a wry, unassuming little man with a perpetual gleam in his eye and the rarest of human touches.

He was also a walking monument to Reds history. Stowe joined the Reds as a bat boy in 1947 when he was 12 years old, and filled that role for the National League team at the 1953 All-Star Game at Crosley Field. In a 2005 interview with the Dayton Daily News’ Hal McCoy, Stowe recalled how Rogers Hornsby, the irascible Reds manager, enlisted him to throw batting practice during the 1953 season only to chase him off the mound because he threw like a “sissy.”

Stowe ascended to the role of clubhouse manager in 1968, and everyone in Reds-land knew who was in charge. When Sparky Anderson replaced Dave Bristol as Cincinnati manager in 1970, Stowe allegedly told him, “Let’s get one thing straight. I was here before you got here and I’ll be here after you’re gone, so don’t give me any crap.” While the comment was more joke than boast, it turned out to be prescient. Stowe was with the Reds through manager Fred Hutchinson’s cancer, Frank Robinson’s MVP season and the Big Red Machine’s title runs in the 1970s. He was there for the rise and fall of Rose, Schott’s troubled and chaotic regime, and the two decades of mostly mediocre baseball that have played out since.

Cincinnati players through the years recall his fondness for clubhouse pranks — most notably, the “mongoose” gag. Stowe brought in a padlocked steel cage and stamped it with signs reading “Danger, Wild Mongoose.” He talked up the alleged viciousness of the sleeping creature inside while banging on the sides to build suspense. When he finally popped the door to the cage and a faux tail came flying out, petrified rookies scattered to all corners of the clubhouse.

Players also reveled in Stowe’s running comedy routine with the late Reds pitcher and broadcaster Joe Nuxhall. Each day, like clockwork, Nuxhall would arrive at the park and ask about the “slop” Stowe planned to serve in the postgame food spread, and Stowe would respond by needling Nuxhall for his mangled syntax in the booth. Joe called Bernie “Chubby the Clubby,” and Bernie called Joe “Old Marble Mouth,” and they shared an encyclopedic knowledge of Reds history. If Nuxhall summoned the name of an obscure Reds outfielder who couldn’t hit a curveball, Stowe would instantly recall what model car the player drove, or make a casual aside about his body odor.

“I looked forward every day to the Bernie Stowe-Joe Nuxhall show,” Casey said. “It was like Abbott and Costello.”

Beyond the gags and frat-house bonding, Stowe dispensed words of wisdom and perspective to anxious young players. Many came to regard him as a second father. This is not uncommon in the insular world of the clubhouse. During his Hall of Fame acceptance speech in 2015, Craig Biggio recalled his memorable first encounter with Astros clubhouse man Dennis Liborio, who became one of his best friends in the game. On that same stage in Cooperstown, inductee John Smoltz called the Atlanta Braves’ clubhouse attendants “the heart and soul of our team.”

In the good old days before teams employed three trainers, a massage therapist, strength and conditioning coaches, interpreters, video coordinators, chiropractors and mental skills coaches, Reds trainer Larry Starr did his part to keep the players healthy and the traveling secretary made sure they arrived at the park on time. And Stowe applied the countless touches that made a clubhouse feel like home.

“Bernie was the guy who kept it light and made it a family atmosphere,” former Reds pitcher Tom Browning said. “He made it our place.”

Because Stowe always gave, the players did their best to give back. In January 2015, Casey appeared as featured speaker at the annual winter sports stag for Stowe’s beloved Elder High School on Cincinnati’s West Side. He told stories and cracked jokes for an hour, pausing every few minutes to exhort the crowd to “raise one up” for one person or another. The 750 attendees cheered and hoisted their beer steins in unison. And they were joined by Stowe, who took part in the revelry even though his health was starting to fade.

In November, Casey was honored at an annual Joe Nuxhall fundraiser in Cincinnati. Among those who showed up on a cold fall night to celebrate the occasion: Stowe, his wife, Priscilla, and their sons Rick and Mark.

“I know Bernie had to grind it to be there,” Casey said. “I was so appreciative. I just wanted to hug him and talk to him.”

Stowe was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease nine years ago, and fought the good fight until he was admitted to hospice care in mid-January. As his days dwindled and his family tried to make him comfortable, the intent was to keep things quiet and prepare for the inevitable.

But word of Stowe’s illness gradually leaked out, and players responded in droves. Johnny Bench and Pete Rose reached out to express their concern, and they were followed by Joe Oliver, Ron Oester and broadcaster Marty Brennaman. When the Reds held a fantasy camp in Arizona, Lee May, Tommy Helms, Tom Hume, Billy Hatcher and Chris Hammond were among the former Cincinnati players who appeared in a video wishing him the best. The hospice’s caregivers held a phone to Stowe’s ear, and five or six players got on the line to tell him they loved him.

The old Reds teams had some egos and factions, but they were bonded by a fondness and respect for Stowe. They knew, to a man, that it was reciprocated.

“He loved every one of them,” Rick Stowe said. “He didn’t care if it was the 25th guy on the team, or Johnny Bench or Pete Rose. He treated them all the same. My dad’s motto was, ‘Treat everybody the way you want to be treated.’ And he lived that. He really did.”

Memories of the good times will endure for Priscilla, Stowe’s wife of 58 years, and his four children, Mark, Rick, Jeff and Kim. And the stories will be passed down to his 12 grandchildren, who will take solace in his understated and enduring impact.

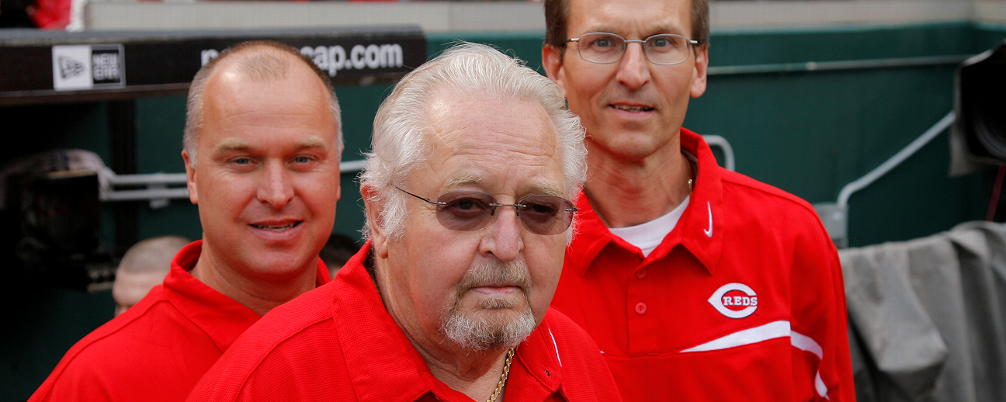

Baseball remains a family affair for the Stowes. Rick runs the home clubhouse at Great American Ball Park, and Mark is the visiting clubhouse manager, and they continue to make sure the players’ stomachs are full and their uniforms are spotless, their ticket requests are fulfilled and their family needs are addressed. Their dad taught them that no aspect of the job is too trivial to overlook.

In 2003, the Reds paid tribute to Stowe by naming the Great American Ball Park clubhouse in his honor, but the place will never be the same without his caring touch. He leaves a bigger void than he could have imagined.

Clubhouse Manager of the Year

Brad Grems San Francisco Giants Home Clubhouse Manager of the Year

Clubhouse Manager of the Year

Gavin Cuddie San Francisco Giants Visiting Clubhouse Manager of the Year