By MARIA TORRES STAFF WRITER NOV. 16, 20204:53 PM

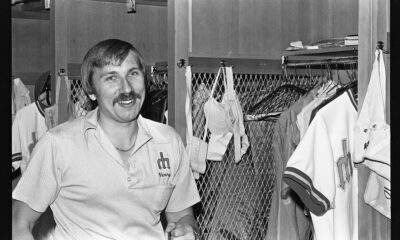

The image of his sons lying on a rug in the basement of a stadium in Arlington, Texas, has never left the mind of Zack Minasian.

For two decades, he managed clubhouses for the Texas Rangers. For two decades, Perry, Zack Jr., Calvin and Rudy took turns helping him.

And during a good chunk of those years , Perry and Zack Jr. spread themselves out on the floor to play their own makeshift version of fantasy baseball. They would draft teams based on a set of rules.

“They would do salary caps and have a budget for each team,” the elder Minasian said. “It was involved — and they were kids.”

The boys — Perry was the second-oldest of the four brothers, Zack the youngest — challenged each other to pick only left-handed hitters or players from a particular division. They wrote down their selections. Their father described Zack Jr. as “very detail-oriented” and Perry as more willing to take risks.

The games transcended the clubhouse. They drafted on planes. They drafted at the dinner table.

“Our mother was disgusted,” Perry said with a light-hearted tone.

Before long, they were doing those things in real life as trusted members of major league front offices.

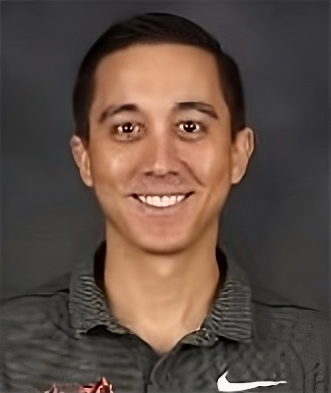

The baseball chats between brothers are about to take on a different life. Last week, Perry was named the Angels general manager. He is entrusted with turning around the course of a team that has not experienced much glory beyond Mike Trout’s shimmering resume over the last decade.

On the day his brother was hired by the Angels, Zack Jr. reflected on their baseball philosophies.

“I think Perry is the type who really isn’t going to box himself into one way of thinking,” said Zack Jr., assistant GM and director of professional scouting for the San Francisco Giants. “He’s really trying to evaluate every option in front of him as thoroughly as possible.”

Perry on Tuesday will participate in his first news conference as the Angels GM. He has never held the title before, and reporters undoubtedly will ask him about his credentials.

He won’t need to rear back too far for the answer. Perry, 40, has spent three-quarters of his life — going from bat boy to scout to executive — cementing his place in the game.

Before he put future All-Star pitcher Noah Syndergaard on the radar of the Toronto Blue Jays in 2010, before he helped recruit MVP contender Josh Donaldson to Atlanta, before he wowed Angels President John Carpino in a video interview and owner Arte Moreno in an in-person meeting, Perry Minasian charmed Bo Jackson.

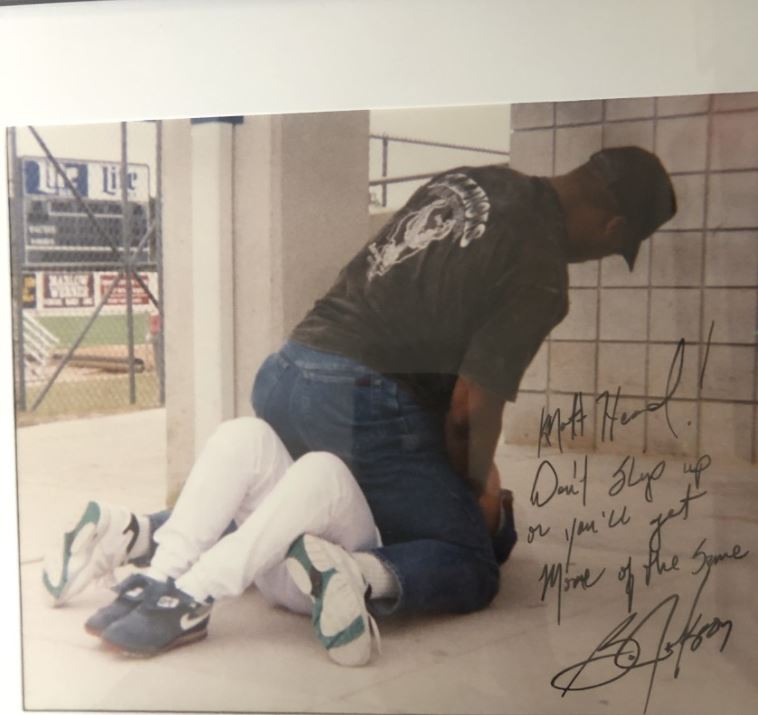

There is an autographed photo of the burly superstar on the wall of Perry’s parents’ home in Chicago. It is of Jackson in street clothes, crouching on cement at a spring-training complex over a prone Perry. All that is visible of Perry is his uniformed legs.

“Meathead,” Jackson inscribed in cursive, “don’t slip up or you’ll get more of the same.”

Jackson formed a bond with Perry and his brothers in the visiting clubhouse when he traveled to Texas. He wasn’t the only one.

Near the mounted picture is a framed front page of the Dallas Times Herald from June 12, 1990. Above the fold is a photo of Nolan Ryan holding a towel to his face in the dugout in between innings of his sixth career no-hitter. Just over his shoulder is a stout young Perry, blowing a gum bubble in his Rangers road uniform.

Perry said on Angels radio last week in his only public comments since his appointment that he revered the Hall of Fame pitcher, who was always generous with his time.

Then he rattled off a list of other major league players, coaches and executives as he shared memories of his unique upbringing.

The Minasians didn’t allow their kids into an MLB clubhouse thinking they’d set them up for careers in front offices across the league.

“I wanted them to have fun,” said Barbara, who took an office job with American Airlines to facilitate the family’s travels around the country after leaving grandparents and others behind in Chicago when Zack Sr. was employed by the Rangers. “That’s what I think children should do.”

Baseball just happened to run in their blood, too thickly for three of them to shake — Rudy is a lawyer; Calvin is a “mini Zack,” running clubhouses for the Washington Nationals.

(Courtesy of the Minasian family)

Before marrying Barbara and settling briefly in Chicago, Zack Sr. rubbed elbows with celebrities and star athletes in Los Angeles. His father, Edward, worked at the Ambassador Hotel.

Edward became close to Tom Lasorda. When Lasorda was hired to his first managerial job in the Dodgers organization in 1966, he asked a teenage Zack to run the clubhouse at rookie-level Ogden (Utah). Zack forged long-lasting bonds during three years there, including his friendship with a young Bobby Valentine.

About 20 years later, when the job of clubhouse manager came open in Texas in the late 1980s during Valentine’s tenure as the Rangers skipper, Minasian returned to the clubhouse with his oldest kids in tow.

“Did I need them? No, not really,” Zack Sr. said. “Did I want them? Yeah. … Looking back on those three years in Ogden, and also being able to go to Dodger Stadium and go in the clubhouse there and walk through the clubhouse where Don Drysdale was or Sandy Koufax, the experience of all that I thought was so great for me.

“I just felt like if I could help them experience that, that would be healthy for them.”

Perry’s parents can pinpoint dozens of moments that foreshadowed his future success. But they may not need to look further than the time a college-aged Perry sat in the back of the Rangers’ chartered plane and debated the potential of a young Adrián González.

González recently had joined the Rangers’ farm system and still had not developed a power stroke. Major league players weren’t convinced he’d be a viable first baseman.

“Perry wouldn’t believe them,” Zack Sr. recalled. “He went on and on [and said,] ‘No, no, no. I’m telling you. Adrián González is a good player.’”

González became an All-Star and MVP contender during a 15-year career that included him hitting .280 with a .793 OPS in 735 games with the Dodgers from 2012 to 2017.

After more than a decade helping his father, Minasian transitioned into talent evaluation, served as staff assistant to Rangers manager Buck Showalter from 2003 to 2006 and worked as an advance scout before joining the Toronto Blue Jays’ scouting department in 2009. Not long after he was hired by the Blue Jays, he took over Toronto’s pro scouting department. After nine seasons, he joined the Braves and was reunited with former Dodgers and Blue Jays executive Alex Anthopolous.

Throughout Minasian’s front-office career, baseball increasingly has turned toward statistical analysis and teams have adjusted by hiring top operations people with Ivy League educations. There were 14 such executives in the job of a general manager or president of baseball operations at the start of the 2020 season. Last offseason, two Yale alumni who wrote for Baseball Prospectus in the early 2000s were hired from the Tampa Bay Rays’ front office to lead departments of their own: Boston hired Chaim Bloom and Houston brought in James Click.

To see Minasian — from a more traditional, though still unconventional, background — earn the Angels’ job was comforting for Doug Melvin, a longtime baseball executive who was general manager of the Rangers from 1994 to 2001.

“Sometimes people have never been around the clubhouse enough and feel uncomfortable going down there,” Melvin said. “He will [feel comfortable] and he’ll know when to step back from a clubhouse. … He knows when to give players space. He knows that. He’s been through those conditions.”

Anthopolous, Minasian’s boss in Atlanta and Toronto, said it took him time to figure out that building a successful team meant more than collecting talent. It meant understanding what makes players tick and how their characteristics can complement others on the field. Anthopolous said he learned the lesson sometime in 2014, after about four seasons as Toronto’s general manager.

Minasian learned that long before he first became an advance scout in 2003.

“It’s like he got to go to college before everybody else,” Anthopolous said. “Everyone was having playdates and things like that. He was in the clubhouse at a young age.”

The Angels are poised to become the beneficiaries of Minasian’s head start.

“He rode home with Johnny Oates every night,” Minasian’s father said, referring to the late major league player and manager who in 1996 led the Rangers to their first playoff appearance. “He drove Johnny home. He picked him up, would bring him to the ballpark. Those little half-hour rides, they were not just rides. They were an education for this kid.

“That doesn’t happen. You don’t get it at Harvard and you don’t get it at Yale. That’s the difference between Perry and who they’ve been hiring.”

Clubhouse Manager of the Year

Brad Grems San Francisco Giants Home Clubhouse Manager of the Year

Clubhouse Manager of the Year

Gavin Cuddie San Francisco Giants Visiting Clubhouse Manager of the Year